The Hidden Wavelength: Understanding Artificial Blue Light & Its Impact on Health

By Jessica Karvelis (BHSc Nat) (AdvDip) (CertIV)

Light is ubiquitous, manifesting in phenomena ranging from the warm radiance of a sunset to the stark brightness emitted by modern electronic displays. While light plays a fundamental role in sustaining life, a specific segment of the visible spectrum, artificial blue light, warrants particular scrutiny.

In this article, we examine the properties of artificial blue light, differentiate between its natural and artificial sources, and, most critically, evaluate the physiological consequences associated with excessive or improperly timed exposure.

Understanding Artificial Blue Light & Why It Matters

Blue light is simply light in the short-wavelength portion of the visible spectrum (generally around 400–500 nm) [1]. During daylight hours, blue light regulates our internal clock, improves alertness, reaction time, mood and cognitive performance [1]. However, the problem begins when artificial sources of blue light, such as LED lighting, screens, tablets, smartphones, laptops, etc, supply blue light at the wrong time (especially in the evening) or in excess. Modern LED lighting and electronic screens emit significant amounts of high‑energy visible (HEV) blue light—generally wavelengths between roughly 380 nm and 500 nm. Excessive exposure in the evening can interfere with our biological systems and disrupt normal brain and hormonal signalling.

Modern Life Has Amplified Blue Light Exposure

The human body evolved under the rising and setting of the sun. Our natural circadian rhythm is tightly controlled by external light cues which is detected by a part of the brain in the hypothalamus called the suprachiasmatic nucleus, the brain's ‘master clock’.

Today, indoor LED lighting and “cool white” fluorescents produce more blue-rich light than traditional incandescent bulbs [2]. Screens (phones, tablets, computers) are frequently used far into evenings, often in dim settings and our exposure to natural daylight (especially outdoors) has been reduced, while exposure to artificial blue light at night is elevated. This shift creates a mismatch between our “light-environment” and our evolutionary biological rhythms.

The Physiological Mechanisms: How Blue Light Influences Your Body

1. Circadian Rhythm & Melatonin Suppression

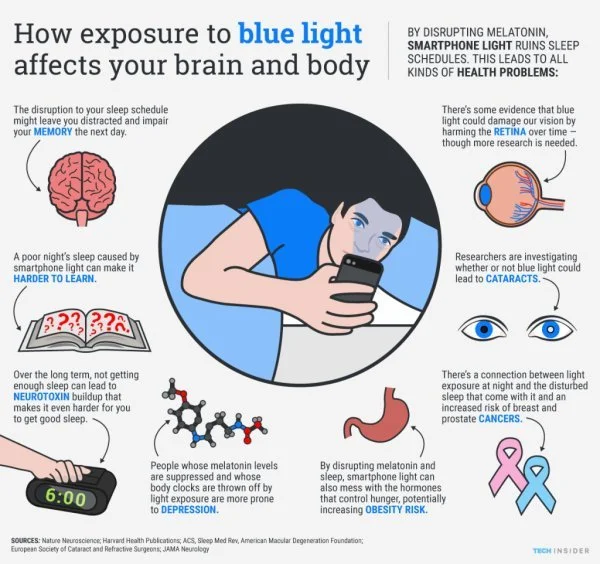

One of the primary ways artificial blue light affects our physiology is through the circadian rhythm and the hormone melatonin. Exposure to artificial blue light at night significantly suppresses melatonin production and release into the bloodstream compared other wavelengths. Artificial blue light exposure in the evening has been shown to shift the circadian phase by nearly 3 hours by suppressing melatonin production, resulting in delayed sleep onset and a decline in sleep quality [3][4].

2. Sleep Disruption → Downstream Health Effects

When blue light disrupts sleep and the body’s natural circadian rhythm, a cascade of downstream effects occur. There is emerging evidence linking disruption of circadian rhythms to increased risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and certain cancers [1], as well as metabolic dysregulation (insulin resistance, impaired glucose tolerance), leading to hormone imbalances such as PCOS, endometriosis and infertility [5].

3. Eye Health & Visual Strain

Blue light is seen paired with ultraviolet A (UVA), and it becomes a problem when it is in isolation. Artificial blue light remained isolated, which makes the human body’s skin pigment pale by degrading melanin, where your photoreceptors reside [6].

Although exposure to blue‑wavelength light during day-light hours supports alertness, attention and cognitive processing, issue arise when blue light exposure continues into the evening or night, when our biology expects lower‑blue (warmer) light and a darker environment. The mismatch between artificial lighting and our evolved rhythms is the core problem. Additionally, there is concern that very high doses of blue light may contribute to retinal damage or accelerate macular changes [7]. Artificial blue light exposure has been shown to destroy photoreceptors of the eyes and promote eye strain, dry eyes, blurred vision, and fatigue [4].

4. Timing Matters: Daytime vs Nighttime Effects

Importantly, blue light is not inherently “bad” — timing is everything. Artificial blue light should be avoiding in the mornings and evenings, as exposure close to waking can decrease melatonin production, as melatonin is synthesised from the exposure to UVA light. At least 2-3 hours after sunrise/waking is the safest time for artificial blue light exposure. After sunset, artificial blue light exposure becomes disruptive, as such wavelengths signal “day” to our systems when we want “night”. Therefore, our cortisol rises, digestive secretions are turn on, insulin and blood pressure increases. However, these functions should decrease or stabilise in the evening, to allow melatonin release, detoxification and autophagy.

Practical Strategies: Protecting Your Biology from Excessive Artificial Blue Light

Daytime Habits

Make sure you receive ample natural daylight exposure—this helps synchronise your circadian rhythm.

Use built‑in “night mode” or “warm display” features on digital devices as the day progresses.

Adjust screen brightness to match ambient lighting; reduce glare and excessive contrast.

Use the “20‑20‑20” rule: every 20 minutes, take a 20‑second break and look at something ~6 metres away to reduce visual fatigue.

Aim to get natural daylight exposure (preferably in the morning) — 20 minutes or more outdoors is ideal. Expose as much skin as possible and do not wear sunglasses during this time as your eyes contain photoreceptors that detect the wavelengths coming from the sun that will regulate your circadian rhythm, steroid and thyroid hormones, and melatonin production.

During the day, allow bright ambient light into your environment from the sun. If you require more brightness in your environment, use indoor lighting that has a warmer temperature (i.e., salt lamp).

Evening & Night‑Time Protecting

After sunset, reduce overhead lighting, switch to warm/amber‑toned lamps, and minimise screen time.

Activate night‑shift or blue‑light‑reduction modes on devices. Install a red screen app onto your devices - flux.e or Iris.

Consider wearing blue‑light‑blocking glasses if you must use screens late; these significantly attenuate blue (and sometimes green) wavelengths that impair melatonin production.

Ensure your bedroom environment is dark (reduce ambient LED lights, charging‑station lights, etc.) and cool. Consider blackout curtains, no night-lights.

General & Long‑Term Habits

Maintain consistent sleep‑wake times to support stable circadian rhythms.

Build an evening “wind‑down” routine: lower lighting, low‑stimulus screen use, perhaps reading with a warm‑light lamp.

Use ergonomics: position screens and lighting to minimise direct glare; ensure ambient lighting is balanced rather than harsh overhead.

Support Bio-Systems Through Nutrition & Lifestyle

Because artificial light exposure accentuates oxidative stress by destroying the photoreceptors in the skin and retina, this may impact hormonal/metabolic systems. Therefore, include dietary and lifestyle support such as:

o Antioxidant-rich foods (berries, leafy greens, coconut oil, olive oil, activated nuts/seeds) to buffer oxidative damage.

o Sleep-hormone regulators: magnesium glycinate, high-quality protein, zinc, methylated B-vitamins, passionflower, California poppy.

o Prioritise regular physical activity and stress-management (meditation, breathwork, nature walks, barefoot walk – grounding, minimise non-native EMF exposure).

o Screen‐time breaks: For those using screens for extended periods, adhere to the 20-20-20 rule: every 20 minutes look at something ~20 feet away (~6 m) for 20 seconds. This helps reduce eye strain [11].

Consider Shift-Work or Evening Screen Use Special Protocols

If you work evening shifts, or you are a heavy screen-user at night, more conscious protocols are needed, such as:

o Intentionally shift your “light exposure window”: use bright light (even blue-rich) during their “daytime” (even if that is evening) and reduce lighting during the “night”.

o Use warm lighting in living/bed spaces, avoid bright screens close to bedtime, adopt a strict pre-sleep light-down routine.

o Address other lifestyle factors (meal timing, caffeine/alcohol, sleep environment) that may exacerbate the light-induced disruption.

Light is not just for vision — it’s a powerful signal to your body. The wavelengths, intensity, timing and quality of light influence your biological rhythms, hormones (especially melatonin), metabolism and repair systems. Evening light matters more than you realise. It’s not just about how long you slept, but how well your body recognised “nighttime” and artificial blue-rich light in the evening disrupts that recognition process. Simple changes = high leverage. Adjusting lighting habits, screen behaviours and ensuring darkness during the sleep window is a high-impact, low-cost intervention.

Trusted Australian Suppliers for Amber / Blue‑Light‑Blocking Glasses

Below are several reputable vendors that offer amber‑tinted or high‑block blue‑light glasses.

BlockBlueLight: Based in Australia, many amber‑lens models and sleep‑specific versions. For example, their “SunDown Lucent” amber lens claims to block 100 % of blue light.

Soma Sleep: Australian brand with lenses designed for evening use; their amber lens blocks harmful blue‑wavelength (~400‑500 nm) for improved sleep.

Urban Hippeee: Queensland‑based family‑run business (Brisbane) offering amber‑lens sleep glasses with strong blocking claims.

Rhythm Optics: Higher‑end Australian brand for advanced light‑filtering eyewear—with lenses blocking beyond blue into green wavelengths.

RA Optics: Premium international brand marketed in Australia.

Purchasing Tips

Check the wavelength range the lenses block (e.g., “blocks 100% of 400‑500 nm” or “blocks blue & green up to 550 nm”).

Decide on tint: clear lenses do not block out blue and green pigments, even if their marketing says otherwise.

Ensure you are also practising good habits (lighting control, device settings) — glasses are an adjunct, not the whole solution.

‘

As a naturopathic practitioner, the concept of light, especially artificial blue light, is a potent but often overlooked factor in health. Gone are the days when we only worried about what we ate, how much we moved, and how much we slept. The quality, timing and spectrum of light we expose ourselves to is a fundamental pillar of circadian health, hormonal balance, metabolic function and visual/skin health.

Incorporating light hygiene into your protocol, alongside diet, movement, sleep and stress management, empowers you to take control of a hidden yet powerful environmental influence. The evidence is still evolving, and there are debates and some limitations to our knowledge, but the risk-versus-benefit calculation strongly favours prudent action: reducing inappropriate evening blue light, aligning lighting with your biology, and supporting the downstream systems affected.

References

Haghani, M., Abbasi, S., Abdoli, L., Shams, S. F., Baha’addini Baigy Zarandi, B. F., Shokrpour, N., Jahromizadeh, A., Mortazavi, S. A. R., & Mortazavi, S. M. J. (2024). Blue light and digital screens revisited: A new look at blue light from the vision quality, circadian rhythm and cognitive functions perspective. Journal of Biomedical Physics and Engineering, 14(3), 213–228. https://doi.org/10.31661/jbpe.v0i0.2106-1355

WellBeing Magazine. [Artificial lighting and blue light exposure]. → https://www.wellbeing.com.au/body/health/artificial-light-health-effects.html WellBeing Magazine

Brainard, G. C., Hanifin, J. P., Greeson, J. M., Byrne, B., Glickman, G., Gerner, E., & Rollag, M. D. (2001). Action spectrum for melatonin regulation in humans: Evidence for a novel circadian photoreceptor. Journal of Neuroscience, 21(16), 6405–6412. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-06405.2001

UC Davis Health. [Sleep quality and light exposure]. → https://www.ucdavis.edu/health/news/zen-and-art-color-quality-0 UC Davis

Fleury, G., & Mascaro, J.-P. (2020). Metabolic implications of exposure to light at night: A comprehensive review. Journal of Biological Rhythms, 35(4), 307–321. https://doi.org/10.1177/0748730420921323

Nakashima, Y., & Ohta, S. (2017). Blue light-induced oxidative stress in live skin. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 108, 112–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.03.010

Salceda, R., & García-Bosque, S. (2024). Effects of excessive blue light on retinal function and oxidative stress: Implications for human health. Antioxidants, 13(3), Article 362. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox13030362